Connect With Authors

*Your message will be sent straight to the team/individual responsible for the article.

In 1988, Brazil adopted a new constitution after over two decades of military rule. The government of Fernando Henrique Cardoso (1995-2002) brought an end to hyperinflation and implemented reforms to liberalize the economy. During the presidency of Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (2003-10), Brazil saw the benefits of these reforms and experienced a consumer-driven boom fueled by commodities. However, this ended and led to unrest due to a weak economy, corruption, and inadequate public services. Lula’s successor, Dilma Rousseff, won a second term in 2014 but was impeached in 2016 for budget irregularities. Her vice president, Michel Temer, completed her term. Jair Bolsonaro won the 2018 election, but lost to Lula in the 2022 second-round run-off election, and Lula took office as president on January 1st, 2023.

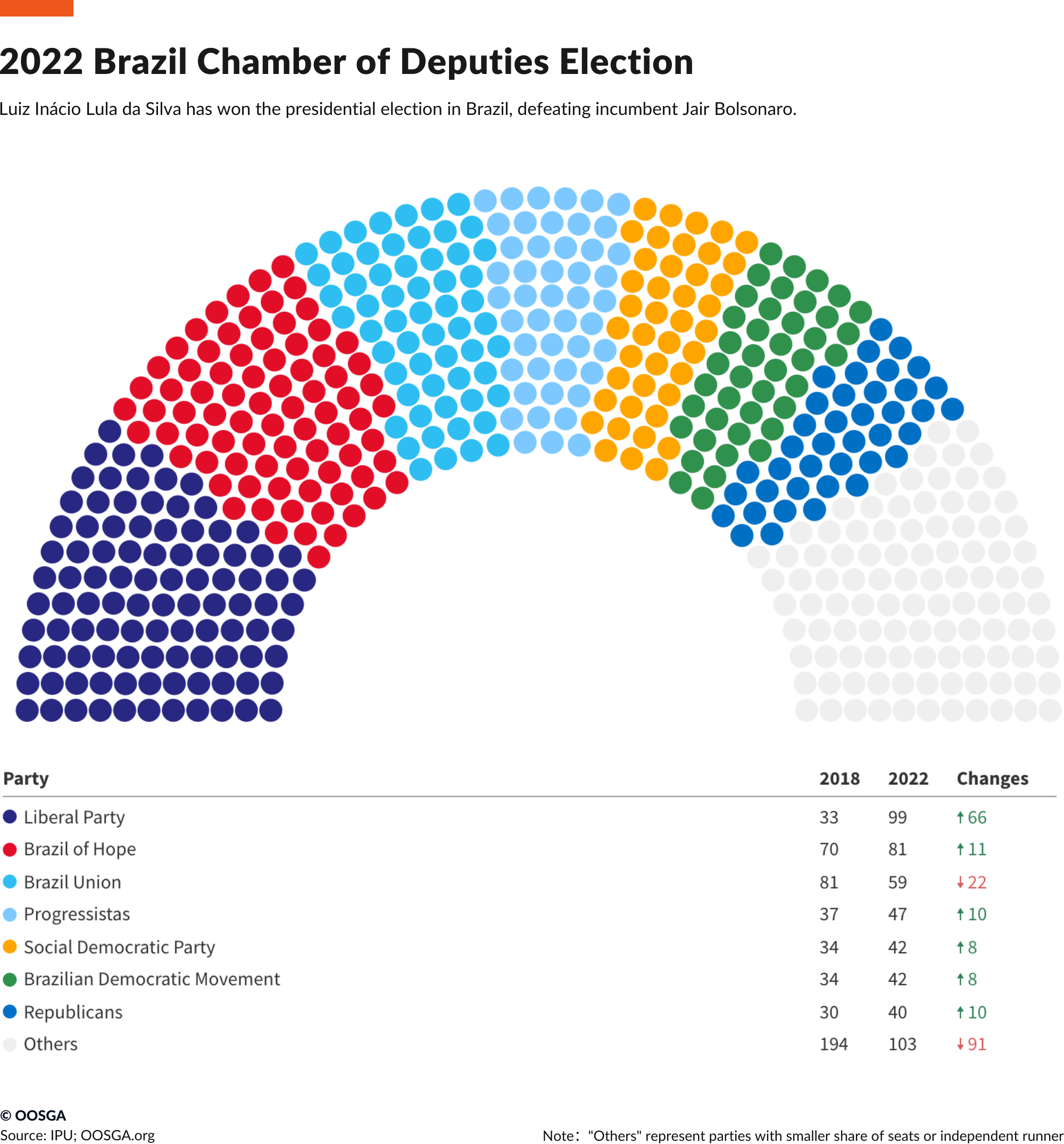

Brazil’s political system consists of a president who carries out policies approved by the Chamber of Deputies, the lower house, and the Senate, the upper house. The judiciary conducts constitutional review and has independence. The president can use temporary decrees to pass legislation, but the constitution provides Congress with ample power to check the executive. The lower house has representation from 30 political parties and has a history of weak party discipline.

The benefits and entitlements established under the 1988 constitution have resulted in a doubling of central government primary spending to over 27% of GDP. In 2016, Congress passed a federal spending cap and in 2019, a robust pension reform was passed. The central bank, Banco Central do Brasil, started a rapid normalization cycle in March, raising the policy rate to its current 13.75%. The government reduced emergency coronavirus spending to less than 1% of GDP in 2022, but fiscal consolidation is progressing slowly. The public debt to GDP ratio was 76.8% in October 2022 and the fiscal deficit was 4.2% of GDP.

-53.62 Billion

-2.8 %

-3.1 %

85.3 %

Former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva was elected as Brazil’s new President, ousting Jair Bolsonaro after just one term. The election result marks a major political revival for Lula and signals the end of Bolsonaro’s turbulent time as the region’s most powerful leader. Bolsonaro’s polarizing style and frequent turmoil led millions of Brazilians to tire of his administration. The election results also showed a deep divide in the country, with Lula winning by the narrowest margin of victory in the 34-year history of Brazil’s modern democracy.

Lula’s victory brings an end to a highly important presidential race between two of Brazil’s biggest political figures and extends a string of leftist victories across Latin America. Despite being viewed as corrupt by a significant portion of the population, the opposition to Bolsonaro’s far-right movement was enough to carry Lula back to the presidency. Lula has vowed to govern for all 215 million Brazilians and not just for those who voted for him, stating that there is only one country, one people, and one great nation. He is set to take office on January 1st.

The new government under President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva is expected to adopt a more interventionist and state-driven economic policy, with increased lending by the state development bank, BNDES. However, Lula is not expected to deviate greatly from the macroeconomic approach under former President Jair Bolsonaro and will maintain the independence of the central bank, Banco Central do Brasil, and the floating exchange rate regime. Fiscal policy will become more expansionary and there may be some political appointments in state-owned enterprises to pursue Lula’s public policy objectives.

Lula’s government is expected to increase social spending and replace the fiscal cap on public expenses with a rules-based framework, leading to a rise in the public debt to GDP ratio and potentially setting back fiscal consolidation. A tax reform to simplify Brazil’s complex tax system, introduce a tax on dividends, and make the tax regime more progressive is a priority for the government in 2023. The impact of the tax burden is uncertain, but it is expected to raise only about half of any extra spending approved for 2023 and subsequent years, meaning the public debt to GDP ratio is likely to continue to rise. New privatizations are not in the cards, but progress on infrastructure concessions is expected to continue. The government will seek targeted changes to labor legislation to expand benefits for remote and informal workers, but is unlikely to overhaul the 2017 reform that made it more flexible.

-

24

-

57

1.28 $

7.15 $

497 $

-0.4625 %