Connect With Authors

*Your message will be sent straight to the team/individual responsible for the article.

As the government grapples with the immediate challenge of offsetting the effects of rising costs for essential items, it is clear that its strategic direction will have a significant impact. Notably, this is occurring despite the fact that the country’s headline inflation rate is considerably lower than some of its regional counterparts. Current subsidies on electricity and fuel are already in place and are projected to remain for an indefinite period. Furthermore, as the headline rate of food price inflation remains at peak levels, price caps on essential food items are likely to be maintained throughout 2023-24.

The government is set to utilize the midterm review of the 12th Malaysia Plan – a five-year financial scheme spanning from 2021 to 2025 – as a platform to establish its medium-term objectives. Slated for completion by September 2023, the review is anticipated to stimulate increased expenditure on infrastructure projects in the subsequent years of 2024-25. A core feature of the plan is the preservation of an initiative aimed at elevating equity ownership by bumiputera. This measure is integral, as its removal could spark the exit of at least two pro-Malay factions from the unity government, potentially instigating a parliamentary crisis.

Anwar Ibrahim, the leader of the multicultural Pakatan Harapan (PH) coalition, helms a unity government, which includes pro-Malay factions. Because of the need to govern alongside their traditional ideological rivals, Malaysia has not yet made a clear shift towards multiculturalism. Ethnic-Malay identity politics continue to wield a significant influence, and their presence within the unity government will limit Anwar’s progressive leanings. He has already committed to maintaining ethnic-Malay preferences, such as increasing their wealth ownership. Any attempt to dismantle these preferences would likely lead to the departure of the pro-Malay faction from the government, jeopardizing the PH’s operational parliamentary majority. This faction is also expected to resist any efforts to cap the tenure of the prime minister to two terms.

Anwar may be successful, however, in implementing anti-corruption measures. These may include separating the attorney-general’s chamber from the public prosecutor, introducing a political finance act, and passing a law to protect whistle-blowers. A law against party-hopping, along with the Barisan Nasional’s (a former ruling coalition) aversion to collaborating with the opposition Parti Islam Se-Malaysia, should enhance political stability in the coming years. The signing of a memorandum of agreement by the coalition’s constituent parties, functioning similar to a confidence-and-supply pact, will support policymaking. Yet, there remains a low risk that the strains of consensus-building could lead to a premature collapse of the government.

Looking ahead, the PH’s triumph in becoming the largest party alliance may appear less substantial. The fall of the well-established United Malays National Organization and the rejection of another pro-Malay party led by former prime minister Mahathir Mohamad have bolstered the prospects of the opposition PAS and the governing Gabungan Parti Sarawak. This could result in a more unified Malay vote in the next election, scheduled for 2027, which may undermine the PH’s standing as a governing party. A lot will hinge on whether Muhyiddin Yassin, the leader of the opposition PN, can rally his party and the PAS against the government. To do this, he will have to appeal to ethnic-Malay identity, particularly in rural areas. The division of Malay loyalties between the PPBM and the PAS may be crucial in preventing the PAS from monopolizing the rural and conservative Malay votes in the upcoming election. While Yassin might be successful, this could likely stoke ethnic tensions in the long term, resulting from disagreements over ongoing affirmative action policies favoring bumiputera. As Anwar seeks to avoid this, his scope for action remains constrained at the helm of a large and potentially unwieldy governing coalition.

12.52 Billion

3.1 %

-5.9 %

65.6 %

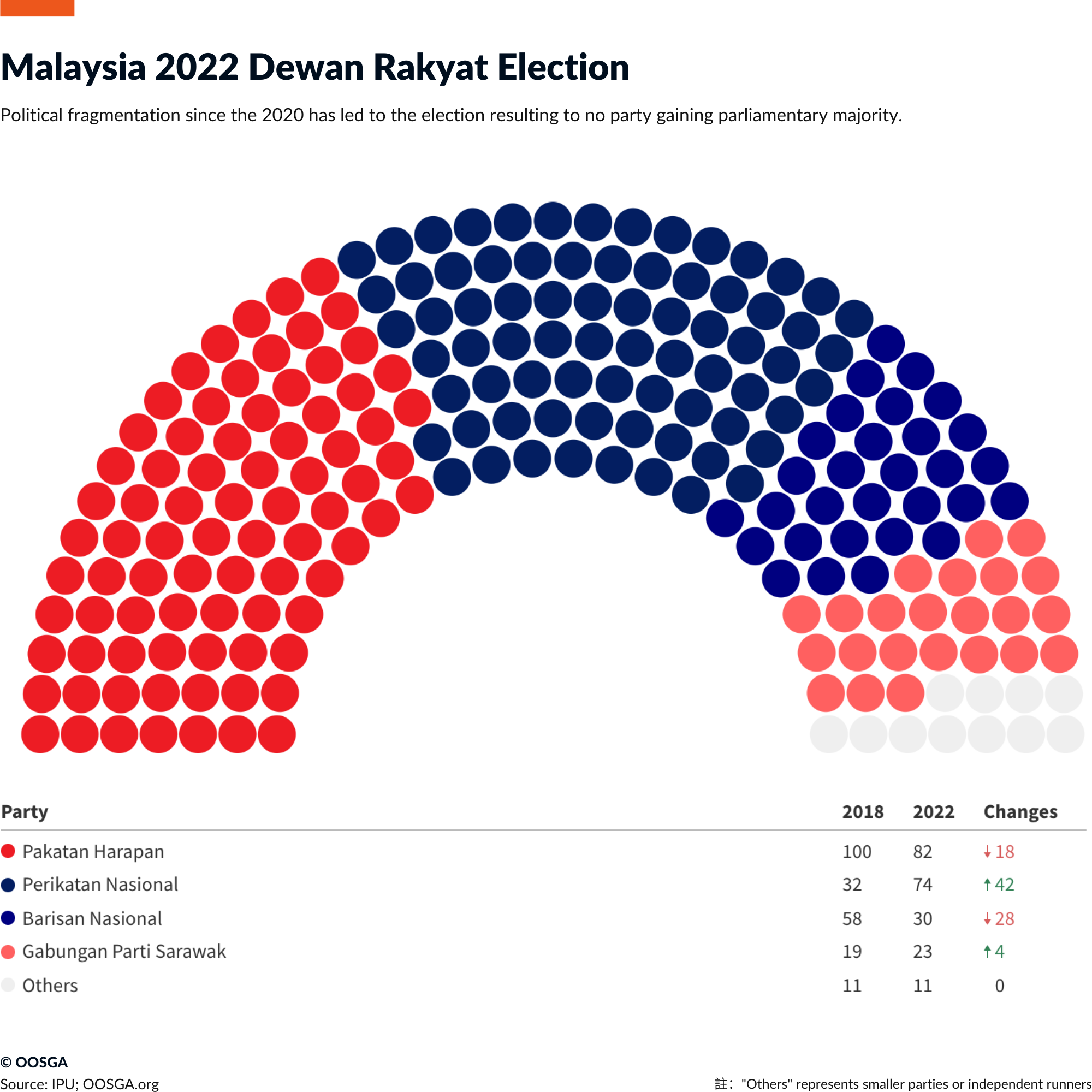

Malaysia held general elections on 19th November 2022 amidst an ongoing political crisis triggered by coalition or party switching among members of Parliament, compounded by the fallout of the COVID-19 pandemic. This instability had led to the resignation of two prime ministers and the collapse of their respective coalition governments since the 2018 general elections. The term of the 14th Parliament was due to end on 16 July 2023, but at the behest of Prime Minister Ismail Sabri Yaakob, the Yang di-Pertuan Agong (King of Malaysia), Abdullah of Pahang, dissolved the parliament on 10 October 2022. This meant elections had to occur within 60 days of the dissolution, with 9 December set as the last possible polling day.

While historically, general elections for all state legislative assemblies of Malaysia except Sarawak were held simultaneously to save costs, the political instability had led several states to hold early elections. These states, along with Sarawak, indicated they would not be holding state elections concurrently. Some other states, particularly those under a Pakatan Harapan or Perikatan Nasional government, expressed a preference for completing a full term. In these elections, for the first time, 18-20-year-olds were eligible to vote, after a constitutional amendment reduced the voting age from 21 to 18. All voters were automatically registered, leading to a 31% increase in the electorate.

The elections resulted in a hung parliament, the first time such an outcome has been seen in a federal election in Malaysia’s history. Pakatan Harapan remained the coalition with the most seats in the Dewan Rakyat, though with a reduced share. In contrast, the historically dominant Barisan Nasional fell to third place, losing most of its seats to Perikatan Nasional. After obtaining support from Barisan Nasional and other parties, Pakatan Harapan chairman Anwar Ibrahim was appointed and sworn in as Prime Minister on 24 November 2022, while Perikatan Nasional opted to become the official opposition.

The upcoming national election is scheduled for 2027. However, the state elections in Penang, Selangor, Negeri Sembilan, Kedah, Kelantan, and Terengganu, which usually coincide with the national election, are poised to introduce some political uncertainty in 2023. The elections for these six state assemblies are expected to be staggered starting from April 2023, though there’s also the possibility of a unified polling date. Furthermore, four additional state elections are set to occur before the next general election; the Sabah state assembly’s term is due to end in 2025, with three more state assemblies’ tenures expiring in 2026.

-

30

The political environment in Malaysia is expected to worsen in the coming years, with continued fragmentation that has been present since the 2018 election. It is difficult to predict a secure parliamentary majority for any future government, leading to instability and weaker political effectiveness. The macroeconomic environment is also expected to decline compared to the last five years, with a return to pre-pandemic levels in 2022, but at the cost of deterioration in public finances and an increase in debt levels. The external environment has become more challenging with high inflation and tighter monetary policy, making conditions for Malaysia’s exporters more competitive.

Despite the negative outlook, there are positive developments. The market is expected to improve, with Malaysia becoming the third-ranked Asian economy behind China and Australia. This is due to long-term trends such as increasing wealth among Malaysians and deeper regional integration through membership in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and the launch of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). Investments in digital infrastructure will also boost the score for infrastructure, while reduced trade tariffs are expected to enhance Malaysia’s policy towards foreign investment.

-

11

1.07 $

2.65 $

673 $

1.21 %